The Many Facets of Liu Kang

Liu Kang’s many roles as photographer, artist, educator and critic helped paint a new narrative for Singapore’s art history.

By Lee Chor Lin

24 July 2025

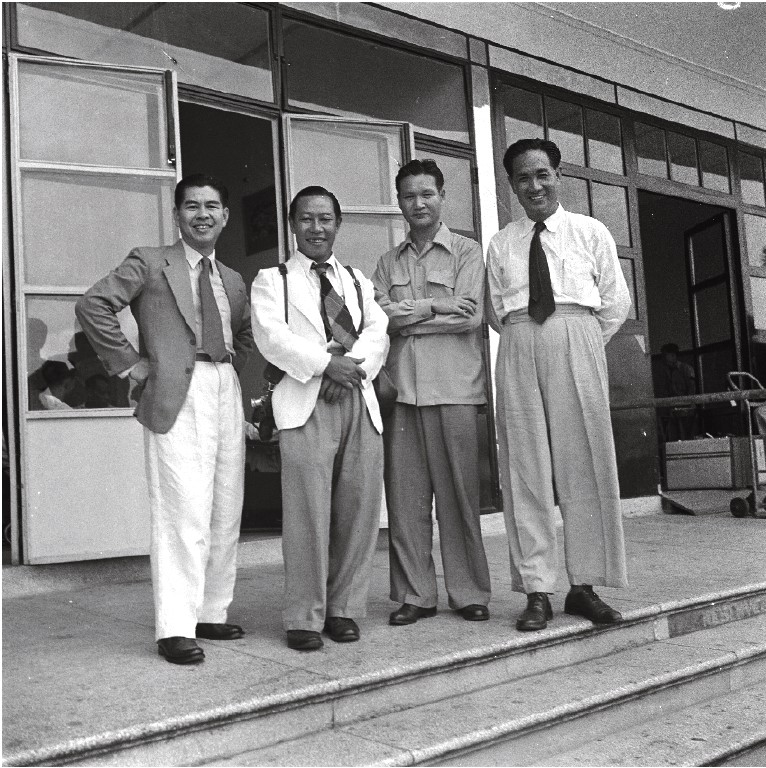

In 1952, four Singapore artists – Chen Chong Swee, Chen Wen Hsi, Cheong Soo Pieng and Liu Kang – embarked on a two-month sketching trip to Java and Bali between 8 June and 28 July. Their aim was to experience and capture a cultural milieu, way of life and landscapes different from what they could find in Singapore. The following year, they presented a group exhibition of more than 100 paintings and sketches arising from the trip.1

The four artists at Kallang Airport for the flight to Jakarta, 8 June 1952. (From left) Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Cheong Soo Pieng and Chen Wen Hsi. © Liu Kang Family.

The four artists at Kallang Airport for the flight to Jakarta, 8 June 1952. (From left) Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Cheong Soo Pieng and Chen Wen Hsi. © Liu Kang Family.The exhibition was warmly received in Singapore when it opened to the public in November 1953. As the editor of Nanyang Siang Pau observed, the crowds visiting the exhibition created a buzz at the otherwise sedate British Council.2 In his oral history interview in the 1980s, Chen Wen Hsi recalled with amusement the reception to the exhibition. “That exhibition broke new ground in Singapore. No one had done something like that before,” he said. “Someone called us the Four Master Painters, but we didn’t know how in the world that came about.”3

The exhibition has since been described as a milestone in Singapore’s art history. The collective experience of the artists was seen as the beginning of a stylistic regionalism that was taking shape. These diasporic China-born artists, who were now in this region for the long haul, were attempting to evolve a new approach of visualisation (or representation) deploying their techniques to capture the indigenous cultural elements they encountered in the larger Southeast Asian environment.

Seven decades on, we are able to reimagine the trip and its artistic consequences in the exhibition at the National Library, Untold Stories: Four Singapore Artists’ Quest for Inspiration in Bali 1952. Presented in this exhibition are field photographs taken by Liu Kang, letters sent home during the trip, as well as some of the artworks presented in their Bali exhibition in 1953. Untold Stories also provides an impetus for us to relook and rethink the many roles that Liu Kang had played in the art scene of Singapore spanning more than 60 years.

The Accidental Documentation

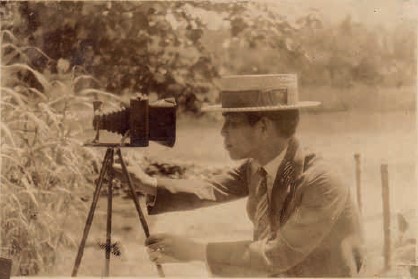

Photography was a skill Liu had acquired from around the age of 15, as he left Singapore to study in Shanghai.4 Thanks to the determination of Gretchen Liu, the daughter-in-law of the artist, Liu’s photographs have been sorted, progressively identified and published in a number of books. Despite Liu’s reluctance to recognise photography as an art form, his photographs are a treasure trove of art history.

The earliest photo of Liu Kang with his camera, Shanghai, 1926. © Liu Kang Family.

The earliest photo of Liu Kang with his camera, Shanghai, 1926. © Liu Kang Family.The numerous images that Liu took during the trip to Java and Bali in 1952 were most probably meant as materials for him to work on. Since the 1930s, Liu had been developing a method very much based on what he understood as being unique to that of Paul Gauguin, the French painter and sculptor whose work has been primarily associated with the Post-Impressionist and Symbolist movements.

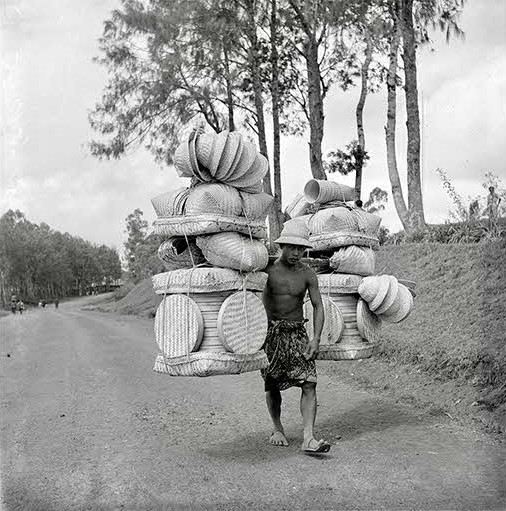

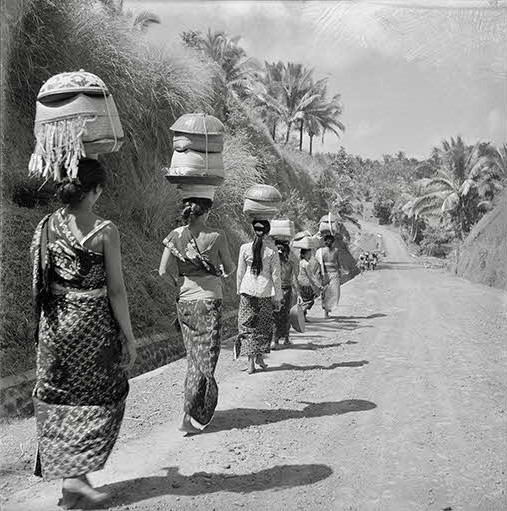

Liu sketched diligently and also took copious photographs of his subjects, not to depict or transpose realistically, but to derive abstract elements from them and reduce them into flattened, minimal and primordial forms.5 Liu’s keen eye captured facets of life, landscape and people in two important sites of Indonesia, a nation newly recovered from the trauma of World War II and a hard-earned revolution for independence after nearly 300 years of Dutch colonial indenture.

Liu’s Bali photographs encapsulate the essence of Walter Spies’ paradisiacal Bali, its highly sophisticated humanity and the meticulously sculpted rice terraces, all on the verge of change.6 As a bonus, the photos also include rare street scenes of Jakarta, the luscious forested and sparsely inhabited hills of Bandung, the padi fields and sugarcane plantations of Central Java, as well as the stunning mountains in East Java. Well composed and skilfully executed, Liu’s photographs are artistic artworks with rich ethnographic content that open a way to reconnect us to his time in Singapore’s art experience.

Inventively arranged, a towering shipment of basketry makes its way to market. © Liu Kang Family.

Inventively arranged, a towering shipment of basketry makes its way to market. © Liu Kang Family.Other art-historically interesting bodies of images are from Liu’s time as an art student in Shanghai from 1926 to 1928; his European sojourn between 1929 and 1933, which included trips to Provence, Geneva, Belgium and Germany with his mentor, the prominent Chinese painter Liu Haisu (刘海粟); and the later years when he taught at the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts (also known as Shanghai Art Academy) between 1933 and 1937.7

Liu Kang painting Liu Haisu’s portrait, 1987. Liu Kang Collection, National Library Singapore.

Liu Kang painting Liu Haisu’s portrait, 1987. Liu Kang Collection, National Library Singapore.Perhaps more precious, due to the turbulence of modern Chinese history, are the photographs of Liu as a student at the Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts (or Xinhua Art Academy), and later, as a teacher at the Shanghai Art Academy after returning from Paris. There are group photographs of Liu and his classmates, and also of sketching trips to destinations around Shanghai, as well as of the groundbreaking nude sketching classes that took place in the academy.

Among the students at the Shanghai Art Academy, those from Fujian, where Liu’s family originated, formed a critical mass. They had their own club, often gathering to send off fellow Fujianese at graduation. These photographs also recorded the presence of artists who later emerged in Southeast Asia and the Society of Chinese Artists (SOCA) such as Yang Eng Kuei (杨永圭), Su Erqi (苏尔琪), Yeo Hwee Bin (杨惠民) and Chen Junwen (陈俊文).

As the writing of Singapore’s art history of the prewar period remains relatively nascent to this day, Liu’s photographs have become much-needed primary sources to understand how the Chinese diasporic artist community functioned at the time, especially after 1937, following the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War that led the young graduates from Shanghai to migrate to Southeast Asia. These academy-trained artists joined more than 200 Chinese schools that had sprung up in Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, primarily to teach art.

Equally important too are Liu’s postwar art scene photographs, including those from the 1952 Bali trip. The historical significance of the art events and their impact on Singapore’s art development are only now beginning to be fully appreciated.8 More gems can be derived from Liu’s vast but still-to-be-catalogued archive of photographs and ephemera. Fortunately, some of his postwar photographs have been deposited with the National Library of Singapore and are progressively being identified in preparation for consultation by library visitors.9

Women formally dressed for a temple ceremony carry their offerings. © Liu Kang Family.

Women formally dressed for a temple ceremony carry their offerings. © Liu Kang Family.What is Nanyang?

The term “Nanyang” (南洋), literally the “South Seas”, was widely adopted by writers of the Chinese language in British Malaya to denote the Chinese diasporic milieu and to describe its geographic and cultural existence in the context of the Straits Settlements, which comprised Singapore, Melaka and Penang. The term was often extended to include Chinese immigrants in Bangkok, the Indonesian archipelago (Dutch East Indies), British North Borneo (Sabah and Sarawak) and Manila.

As the presence of art-engaging Chinese in Malaya grew in number by the second half of the 1930s, exhibitions and performances took place all along the peninsula. These shows travelled by rail from Singapore all the way to Penang, stopping by at Melaka (and/or Muar), Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh and Taiping. Such touring reinforced the notion of an imagined community of diasporic Chinese, united by similar new experiences abroad and the Sino-Japanese War.

With the establishment of institutions such as the Nanyang Girls’ School (1917), the Chinese daily Nanyang Siang Pau by Singapore businessman Tan Kah Kee (1923), the department of Nanyang Studies at Jinan University in Shanghai (1928) and Singapore’s Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts by Lim Hak Tai (1938), the concept of “Nanyang” was made more concrete.

Nanyang was effectively useful as a way to differentiate between China, the homeland, and the realm outside its geographical confines. At the same time, Nanyang suggests the growth of the influence of modern and reformist China, which was reaching outwards via the movement of a now learned professional cohort equipped with modern skills and vocabulary. This cohort also included a great number of highly educated artists who were multi-talented, hungry and eager, many of whom had travelled widely and found themselves in Nanyang. The Singapore-based Chinese art community in the 1930s was one aspiring to integrate itself with the larger world, at least ideologically. Nevertheless, it should be remembered that the term Nanyang was not used in the English medium until decades later.10 Instead, “Malayan” was the term that would conjure up a similar visualisation of the tropicalised milieu in English.

Liu Kang’s Embrace of Nanyang

In its call-for-works notice published in June 1938 in both the Chinese and English media, SOCA appealed to its members “that all exhibits shall be only of recent work of the members and, as far as possible, of Malayan interest”.11 For the years to come, SOCA members would adhere to this motto and help groom two generations of artists who featured Southeast Asian imagery in their works. Liu advocated strongly for this ideal, eager to put into fruition inspirations and stylistic ideas he spent five years pursuing in France.

It was his fascination with the tropics, reinterpreted by the French painter and sculptor Paul Gauguin, that nudged Liu to select Bali as the destination of inspiration in 1952. To him, Bali defined this special sensibility: “Because we went to Bali, everyone came back with a slight change in our styles, which were a bit more novel and richer in Nanyang flavour. There were already hints of it in our past works, though sparse or shallow. After the Bali exhibition, everyone developed stronger personal styles that contained more ‘Nanyang’ character, which attracted a positive reaction from the viewers.”12

Liu continued to produce works of abstracted figures and Gauguinesque colour intensity, while adding brushwork outlines in black pigment to his subjects and figures in the style reminiscent of the French visual artist Henri Matisse. He drew attention to this quality in his speeches, wrote about it in his essays published in the Chinese dailies, but most of all, he consistently painted these “Asian” images he saw in his travels.

In his 87th birthday exhibition, Liu summarised retroactively what he had considered Nanyang style. “One, the subject matter should be of Nanyang: this is largely the tropical region, which one may refer to the definition of ASEAN. However, it should be confined only to scenes of nature and social activities. Highly modernised and industrialised or glamorous commercial areas would not be considered. Two, technique and expression: use plain and lyrical subjective expression to depict the natural or scenes of life, avoid overly objective realist depiction. Three, style and tone: as much as possible use bright and cheerful light and colour palette [sic] to enhance smooth and steady brushwork and lines, so as to portray and to convey the voice of the land and people pivoting between the two hemispheres.”13

Frequent activities such as sketching trips to portray kampong scenes, pre-industrialised neighbourhoods of decrepit shophouses, searching for and painting that Nanyang, and avoiding images of highly developed Singapore were to become the approach of the two generations of artists mentioned earlier. They enjoyed the camaraderie fostered in the art societies, art schools and interest groups. This approach, whether it constituted a collectively conscious style, yielded group exhibitions that were de rigueur in the 1960s and through the 1970s.

While critics have questioned the applicability of “Nanyang” in defining a style, the Nanyang school of grouped sketching trips and resulting artworks has not lost its allure to art interest groups in Singapore today.

The Ten Men Art Group led by art educator Yeh Chi Wei exemplifies a collectively focused methodology of using travel to find innovation, inspiration in form and unprecedented imagery. Between 1961 and 1971, the loose group of 10 artists travelled regularly to various parts of Southeast Asia and showed their interpretations in group exhibitions. Participating artists each maintained highly varied styles and mediums. Every one of these encounters of styles and imageries generated ripples of interest and discussion within and outside the art scene, into which young and new artists were constantly entering, thus effecting more divergence and variety.

In the perceived absence of desirable subject matters locally – the search for subjects which are more colourful, vibrant and exotic – combined with nostalgia for the disappeared streetscapes, idyllic village scenes and lifestyle, travelling and creating imagery of the pre-industrialised and the imagined rural would remain a trajectory of artmaking for years to come.

Leadership and Nurturing Talent

When Liu joined the SOCA in 1938, he was considered a newcomer to a vibrant art scene.14 The SOCA was then helmed by Tchang Ju Chi (张汝器) and U-Chow (庄有钊), the president and vice-president respectively, both of whom had had a 10-year head start on him.

The four-year period leading up to the fall of Singapore in February 1942 was an important time for the Singapore art scene, culminating in art exhibitions by the SOCA and the Singapore Art Society, along with the Fight for Freedom exhibition by the British Department of Information and Publicity in September 1941. At this exhibition, one of Liu’s works in oil was noticed by the press, possibly for the first time. The piece, titled Prawns, was described in the Singapore Free Press as “an amusing, decorative picture of these delicacies, in bright blue, slaty pinks, plaster cream and browns”.15

Unfortunately, World War II wiped out some of the top leadership of the local art world. These include Tchang, U-Chow, Lin Dao’an (林道盦; also a SOCA member) and Ho Kwong Yew (何光耀; an architect and member of the Singapore Art Club), who were killed by the Kempeitai, the military police of the Imperial Japanese Army, shortly after Singapore fell in 1942. The postwar vacuum was filled by Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Chen Jen Hao and Huang Pao Fang, all alumni of Shanghai’s tertiary art institutions.

Liu became president of the SOCA in 1946 and led the society to organise its sixth annual exhibition in December that year, commemorating the fallen artists and forging new paths for the future. He continued to helm the SOCA for a total of 12 years.

In addition to his position at the SOCA, Liu taught art at several schools in Singapore. Like his predecessors, Liu understood that his position demanded that he nurture public interest in art and art education, and be a voice for the artists. Liu put his literary skill to work and published essays from 1947 to the early 1970s in the Nanyang Siang Pau, Singapore’s Chinese-language newspaper of record.

Liu Kang taught art at several schools in Singapore. In 1948, he led the graduating batch of senior high students from Chung Cheng High School on a one-month sketching trip to the Malay Peninsula. Liu Kang is in the first row, second from right. Liu Kang Collection, National Library Singapore.

Liu Kang taught art at several schools in Singapore. In 1948, he led the graduating batch of senior high students from Chung Cheng High School on a one-month sketching trip to the Malay Peninsula. Liu Kang is in the first row, second from right. Liu Kang Collection, National Library Singapore.Some of these essays made a significant impact on the artists he had written about. In 1949, he penned an introductory piece on Chen Wen Hsi’s first exhibition in Singapore. Chen, a fellow alumni from the Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts, had just arrived from Swatow (Shantou), China, and found Liu with help from the ship’s captain. This showed that Liu’s reputation already far preceded him.16

In 1958, to promote the furniture design of fellow SOCA artist Huang Pao Fang, who painted largely Chinese ink works, Liu wrote a piece on Huang’s exhibition in the context of the merits of good design and how great European artists like Picasso dabbled in crafts such as ceramic.17 In the following years, Liu’s numerous art reviews and introductions made him increasingly influential. His writings and views served as a fundamental documentation of Singapore’s art scene, at a time when there were no professional art critics.

To nurture budding artists, Liu supported students and young aspirants in many ways. In 1961, together with Chen Wen Hsi, Liu organised a fundraiser exhibition of works by their star student, the 19-year-old Wong Keen, to send him off to New York where he had secured a place at the Art Students League. A natural teacher, Liu appreciated talent when he spotted them and tirelessly supported those holding their inaugural solos by writing about them. Second-generation artists such as Ng Yat Chuan, Wee Beng Chong, Thomas Yeo, Ng Eng Teng and Tan Choh Tee all name Liu as their first critic.

The longevity of Liu Kang, who passed away in 2004 at age 92, his wide social network, generosity and outgoing personality, and perhaps more importantly, his subconscious understanding of the value of preservation, allows one to review Liu’s life and career as an archive of art history, a rich primary source to be mined and analysed, so that a new narrative of Singapore’s varied art history can be written.

Lee Chor Lin is former senior curator with the Asian Civilisations Museum and former director of the National Museum of Singapore.

Lee Chor Lin is former senior curator with the Asian Civilisations Museum and former director of the National Museum of Singapore.Notes

-

“Bali – By 4 Chinese Artists”, Straits Times, 10 November 1953, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Hua sha mowei luzhou” 化沙漠爲綠洲 [Oasis at the end of the desert], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 10 November 1953, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Transcript of oral history interview with Chen Wen Hsi. See Chen Wenxi, Convergences: Chen Wen Hsi Centennial Exhibition, vol. 2 (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2006), 69. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RART 759.95957 CHE-[LKY]) ↩

-

Gretchen Liu 葛月赞 , “Yi qi feng fa – Liu Kang de zhaopian, geren de gushi” 艺气风发 – 刘抗的照片,个人的故事 (translated from English by Wang Xin) in 艺气风发: 来自刘海粟和刘抗的相册 = Art with Audacity: Photos from the Albums of Liu Haisu and Liu Kang, ed. Gu Zheng 顾铮 (上海: 刘海粟美术馆 及西泠印社出版社, 2019), 11. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 759.951 ART-[LK]) ↩

-

Chia Wai Hon, “Introduction,” in Liu Kang, Liu Kang at 87 (Singapore: National Arts Council and National Heritage Board, 1997), 19. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 759.95957 LIU) ↩

-

Walter Spies was a Russian-born German painter, composer, musicologist and curator who settled down in Ubud, Bali, in 1927 and remained there until World War II. He immersed himself in the exotic world of Bali, and is credited for introducing Balinese culture and art to the Western world. ↩

-

See Liu 葛月赞, “Yi qi feng fa – Liu Kang de zhaopian, geren de gushi.” ↩

-

More than 250 photographs (out of over 1,000) taken by Liu Kang in the 1952 Java and Bali trip have been published by the National Library Board. See Gretchen Liu, Bali 1952: Through the Lens of Liu Kang: The Trip to Java and Bali by Four Singapore Pioneering Artists (Singapore: National Library Board, 2025). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 779.995986 LIU) ↩

-

Goh Yu Mei and Nadia Ramli, “The Liu Kang Collection: A Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man,” BiblioAsia 21, no. 1 (April–June 2025):12–17. ↩

-

See T.K. Sabapathy, “Nanyang Artists and Their Style,” Straits Times, 6 December 1981, 3. (From NewspaperSG). See also by same author “The Nanyang Artists: Some General Remarks” and “O No! Not the Nanyang Again!” in Writing the Modern: Selected Texts on Art & Art History in Singapore, Malaysia & Southeast Asia, 1973–2015 (Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2018), 340–45, 398–403. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 709.59 SAB) ↩

-

“Society of Chinese Artists,” Malayan Tribune, 28 June 1937, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liu Kang, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 13 January 1983, transcript and MP3 Audio, Reel/Disc 40 of 74, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000171), 3. [English version translated and annotated by Tay Jun Hao and Alina Soh.] ↩

-

Liu Kang, “I Am 87,” in Liu Kang, Liu Kang at 87 (Singapore: National Arts Council and National Heritage Board, 1997), 28–29. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 759.95957 LIU) ↩

-

“Huaren meishu yanjiu hui ming wan juxing lianhuan hui didian jia da shijie nei yong chunyuan” 華人美術研究會明晚舉行聯歡會 地點假大世界內詠春園 [The Chinese Art Research Association will hold a party tomorrow night at the Wing Chun Garden in Big World], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 14 January 1938, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mary Heathcott “‘Fight for Freedom’ Exhibition Opens,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 12 September 1941, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liu Kang 劉抗 “Wen xi de hua” 文希的畫 [The art of Wen Hsi], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 17 May 1949, 5. (From NewspaperSG). See also the transcript of Chen Wen Hsi’s oral history interview in Chen, Convergences: Chen Wen Hsi Centennial Exhibition, 103–04. ↩

-

Liu Kang 劉抗 “Huangbaofang de shinei buzhì zhanlan hui nanyang shang” 黃葆芳的室內佈置展覽會 [Huang Baofang’s interior decoration exhibition Nanyang business], Nanyang Siang Pau 南洋商报, 26 April 1958, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩